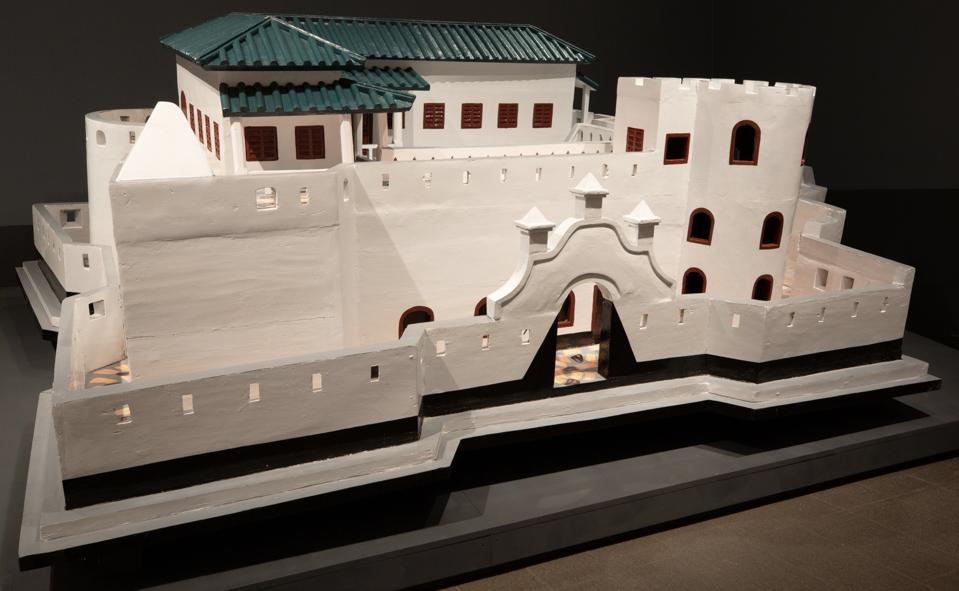

![Paa Joe (Ghanaian, born 1947), '[Fort] Gross - Friedrichsburg – Princetown.' 1683 Brandenburg, 1717 - 24 Ahanta, 1724 Neths, 1872 Britain, 2004 – 2005 and 2017, emele wood and enamel.](https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/5efc829c112bd20006d78044/960x0.jpg?fit=scale)

Paa Joe (Ghanaian, born 1947), ‘[Fort] Gross – Friedrichsburg – Princetown.’ 1683 Brandenburg, 1717 … [+]

Americans, understandably, tend to focus on the portion of the transatlantic slave trade which dropped enslaved Africans on their shores to be sold as a labor force. For all the horrors that aspect of the slave trade produced, atrocities suffered by enslaved Africans were at least matched by the portion of the trade which tore them from their homelands and herded them to transit stations for passage to the Americas in conditions which the mere thought of continues churning the stomach.

Ghanaian artist Joseph Tetteh-Ashong (born 1947), popularly known as Paa Joe, gives shape to the starting blocks of the Middle Passage at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta’s presentation of “Paa Joe: Gates of No Return.” The exhibit features seven large-scale, painted wood architectural sculptures depicting Gold Coast fortresses which served as way stations for millions of Africans sold into slavery and sent to the Americas and the Caribbean between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Having been closed since March, the High reopens to frontline workers and members on July 7, and to the public on July 18, with increased health and safety measures to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

Paa Joe (Ghanaian, born 1947), ‘Fort Patience – Apam.’ 1697 Netherlands, 1868 Britain , 2004 – 2005 … [+]

Joe visited the fortresses he depicts taking pictures and making observational sketches. He didn’t work from detailed blueprints, nor was he interested in exact reproductions to scale.

“He captures their key features, such as Cape Coast Castle’s pentagonal courtyard and Fort Orange’s lighthouse tower,” Katherine Jentleson, the Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art for the High Museum of Art told Forbes.com. “As an experienced and gifted carpenter, he is able to realize his constructions without painstaking preparatory sketches and as he has said himself, with these sculptures, he was most concerned with conveying the emotional experience of these places.”

Cape Coast Castle. Fort Orange. Christiansborg Castle. Fort Patience. Fort St. Sebastian. For enslaved Africans, these were their Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz.

As exhibition materials for the exhibit describe, “once enslaved people were forced through these ‘Gates of No Return,’ they started an irreversible and perilous journey during which many perished and those who survived suffered the spiritual death of permanent displacement and dehumanization.”

How many perished? Much like the Holocaust, an exact figure can never be known. Estimates of 12.5 million seem reasonable.

A tiny fraction of that total are recalled in the High’s exhibit. The names of 730 African people who were forced onto ships from the Gold Coast fortresses are reproduced and memorialized as a reminder to visitors that the slave trade occurred on a human level.

“These names have been recovered by researchers associated with the African Names Database, part of the Slave Voyages project, which uses historical records like ships registers and court documents to reconstruct as much as possible about the transatlantic slave trade,” Jentleson said. “The people named in our galleries were actually on ships that were turned back to Africa after Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807 and began policing the Atlantic basin for ships carrying human cargo.”

The African Names database contains 92,000 entries and is growing.

Paa Joe (Ghanaian, born 1947), ‘Fort St. Sebastian – Shama.’ 1520s Portuguese, 1638 Netherlands, … [+]

Joe is best known for his figurative coffins—or abeduu adekai (“proverb boxes”)—of which he is the most celebrated maker of his generation. In the tradition of his coffins, which are generally commissioned by families and end up in the ground, but have occasionally been commissioned by museums for display, the structures on view in Atlanta represent the unique lives of the dead.

“He sees these sculptures as having a relationship to death—as many people died in the dungeons of these fortresses and millions of others experienced the spiritual death of enslavement and forced displacement,” Jentleson said. “And they are roughly scaled to the human body, like a coffin, but they are meant to stay above ground.”

Since serving as terminals for the transatlantic slave trade, these sites have been used for a variety of purposes. Christiansborg castle was used as the headquarters of the Ghanaian government. Cape Coast Castle is the headquarters for the government’s tourism board. Over the years, others have been schools, a lighthouse, a post office and prisons.

“Paa Joe: Gates of No Return” is on view at the High through August 16.

Paa Joe (Ghanaian, born 1947), ‘Cape Coast Castle.’ 1653 Sweden, 1665 Britain, 2004 – 2005 and 2017, … [+]

Visitors will also encounter a more uplifting work of art debuting there, a one-of-a-kind installation titled “Murmuration” on the Woodruff Arts Center’s Sifly Piazza. The soaring installation created by world-renowned architect and design firm SO–IL, stands as a reflection of the city of Atlanta’s relationship with the natural world–in particular, its reputation as the “city in a forest.”

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel