For more than 40 years, Bernard and Shirley Kinsey have amassed one of the largest private collections of Black paintings, letters, books and other artifacts to teach the next generations what history has erased.

Bernard Kinsey was born to educate. His father, Ulysses B. Kinsey, was the living embodiment of W.E.B. DuBois’ philosophy that a solid liberal arts background was the path to true freedom for Black Americans. After graduating from Florida A&M University in 1941, U.B Kinsey set aside his dream of becoming an attorney to teach at his alma mater, the all-black Industrial High School in Palm Beach, Florida.

That same year, he and other teachers sued the Palm Beach County school board so Black students could attend classes as long as whites and also fought for equal pay for Black teachers. Kinsey’s side won the class-action suit, which was represented by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and, as Bernard Kinsey notes, “that case became one of the building blocks for Brown v. The Board of Education 13 years later.”

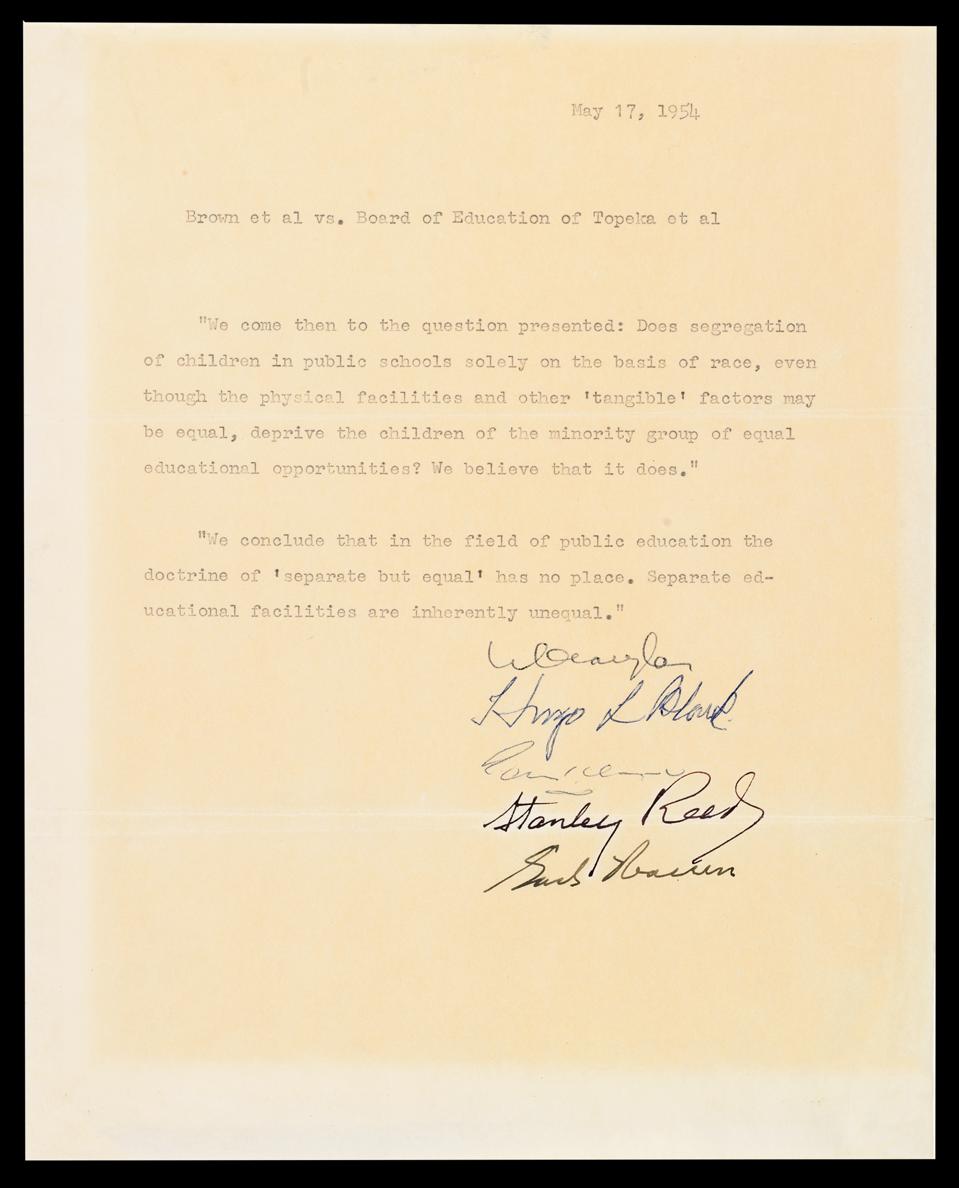

Now 76, Kinsey owns an original copy of the brief from that landmark 1954 Supreme Court case, which ruled that “separate-but-equal” education was unconstitutional and became one of the pillars of the civil rights movement. The Brown brief is part of The Kinsey Collection, an extraordinary repository of art, books, documents and artifacts that chronicle Black America from 1595 to the present.

Judgment Day: The crucial text of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision signed by five Supreme Court Justices.

Brown Et Al. v. Board of Education of Topeka Et Al., 1954

A former Xerox executive and philanthropist, Kinsey—along with his wife, Shirley—started collecting African American artifacts to fill gaps in their son Khalil’s knowledge of Black history. “We saw that Khalil was not getting the right education as it relates to his blackness and in terms of making sure that he understood that he came from a great place,” Kinsey explains. “The whole idea of the Kinsey Collection is achievement and accomplishment.”

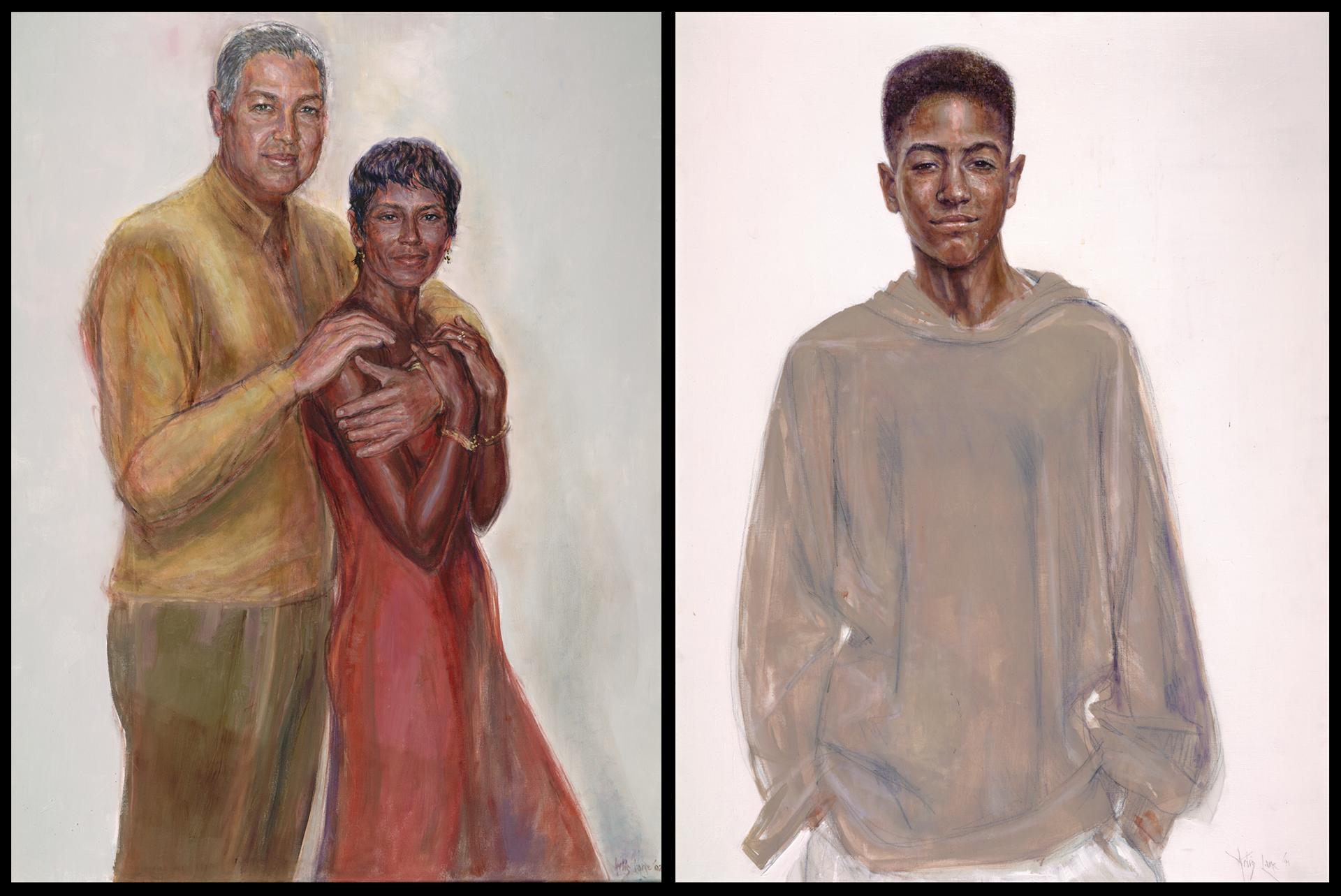

Brush with Greatness: Before painting their portraits, Artis Lane told the Kinseys, “Be casual, because I want to paint you as I know you.”

‘Bernard and Shirley Kinsey’ and ‘Khalil Kinsey’ by Artis Lane, Canadian (b. 1927) (Oil on Canvas)

Their humble intent to show their son that he was more than the legacy of hurt, shame and anger of slavery, has far exceeded the Kinseys expectations. The collection, which he conservatively estimates to be worth more than $10 million and does not have a permanent home, has been seen by some 15 million viewers from Washington D.C. to China since when the family began displaying the collection in traveling exhibits in 2006.

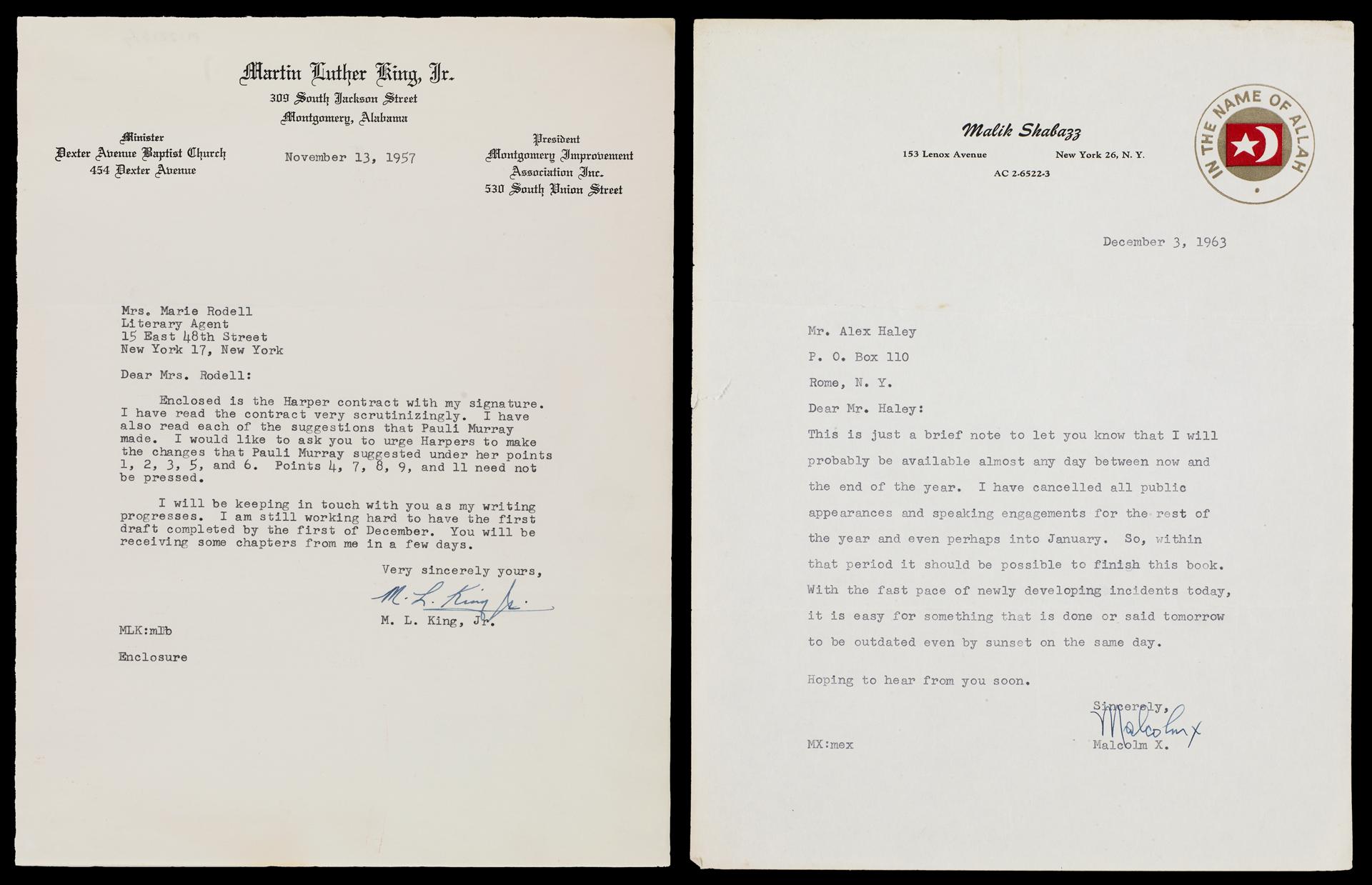

Among the more than 700 treasures the Kinseys own are Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, the first book of poetry published by an African American woman, letters from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, quilts by Bisa Butler, paintings by Richard Mayhew, Alma Thomas, Ernie Barnes, Norman Lewis, and Jacob Lawrence, prints by Ava Cosey, letters from Zora Neale Hurston, and commissioned pieces from friends, such as sculptor Artis Lane.

“[She] is very special to us because we became friends with her before we ever owned any of her pieces,” Shirley Kinsey says. “We used to say we didn’t know if we could afford her because she had done a bronze portrait of Rosa Parks. College friends commissioned her to do a portrait of me and Bernard for our 35th wedding anniversary, she said she always wanted to paint us but didn’t know how we’d feel about it because we said we didn’t want to be hung on a wall. She said, ‘Be casual, because I want to paint you as I know you.’”

Voices of Change: The Kinsey collection features letters from prominent African Americans, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X. and Zora Neale Hurston.

Letter from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to his literary agent, 1957, Letter from Malcolm X. to Alex Haley, December 3, 1963.

To know the Kinseys—who have been married for 53 years—is to understand that theirs was a partnership from the very beginning. They met at a 1963 civil rights protest. Shirley had been arrested and Bernard was part of a Florida A&M University student group handing out supplies to jailed protesters. After Shirley served her three-day sentence, the couple courted over “library dates,” which was a euphemism for leaving campus to watch movies. Since the college cafeteria closed early on Sundays, Bernard made a routine of bringing over shrimp burgers each week. “My friends would tease me about getting to have something to eat that late at night and they told me he loved me before he ever said it,” Shirley Kinsey, now 74, recalls.

Throughout his life, Bernard Kinsey has sought to elevate the black experience and advocated for people who looked like him. After graduating from FAMU, he landed a job at the National Parks Service in 1966, one of the first African Americans employed at the federal agency. After a brief stint overseeing Grand Canyon National Park, he left for a position at Exxon in South Central Los Angeles, 18 months after the Watts Riots.

Kinsey excelled in the position for five years—where his job, among other things, was to make sure the company was in good standing in the mostly Black and Hispanic neighborhood—but he sought more tech-focused work and was lured by Xerox, which was looking for affirmative action hires.

“Even with a B.S in mathematics and an MBA from Pepperdine University going to a liberal company like Xerox it took 12 interviews to be hired,” Kinsey says. “I interviewed for the top job with 100 employees. After 12 interviews I ended up a field service manager with 12 technicians. I found that my managers didn’t even have a college education, in nine months I blitzed the job and they gave me the job I should have had.”

Eventually, he rose to become a vice president of Xerox. Along the way, he cofounded the Xerox Black Employees Association, which paved the way for the company’s first Black female CEO Ursula Burns in 2010. “We have a saying: ‘leave the door open and leave the ladder down,’” Kinsey says. “In other words, at Xerox you couldn’t be successful by yourself, you had to bring brothers and sisters with you, that was part of the ethic that we formed back in 1971.”

Justice for All: “If you don’t solve the problems of the poorest among us,” Bernard Kinsey asks, “how are we ever going to solve these other problems?”

‘Hence We Come,’ Norman Lewis

Just as Kinsey was retiring from Xerox in 1991 another incident of racial violence gripped Los Angeles and galvanized civil rights activists across the country: the brutal police beating of Rodney King. Although King survived and was later awarded $3.8 million for the injuries he sustained, the officers involved in the attack—which was captured on video—were acquitted and the city erupted in violence.

Kinsey responded to tragedy by once again finding a way to uplift the local Black community. He postponed retirement to help found Rebuild LA, a revitalization project for which Kinsey generated more than $380 million in investments from the private sector for inner-city Los Angeles.

“After the ’92 riots, 2,000 building burned, 50 people were killed and police were shooting real bullets, nothing close to what we’re seeing now,” Kinsey says, “and it was unbelievable, anything you could think of was gone. We had to bring those businesses back and they didn’t want to come back because they had lost so much.”

Kinsey leaned on the world he knew best: Corporate America. “If you don’t solve the problems of the poorest among us how are we ever going to solve these other problems,” he says. “Enlightened executives have tremendous resources that they can apply and begin to deploy some of these resources differently. You have to make sure that Black folks, African Americans are the ones in receipt of it, and you’re going to get some backlash.”

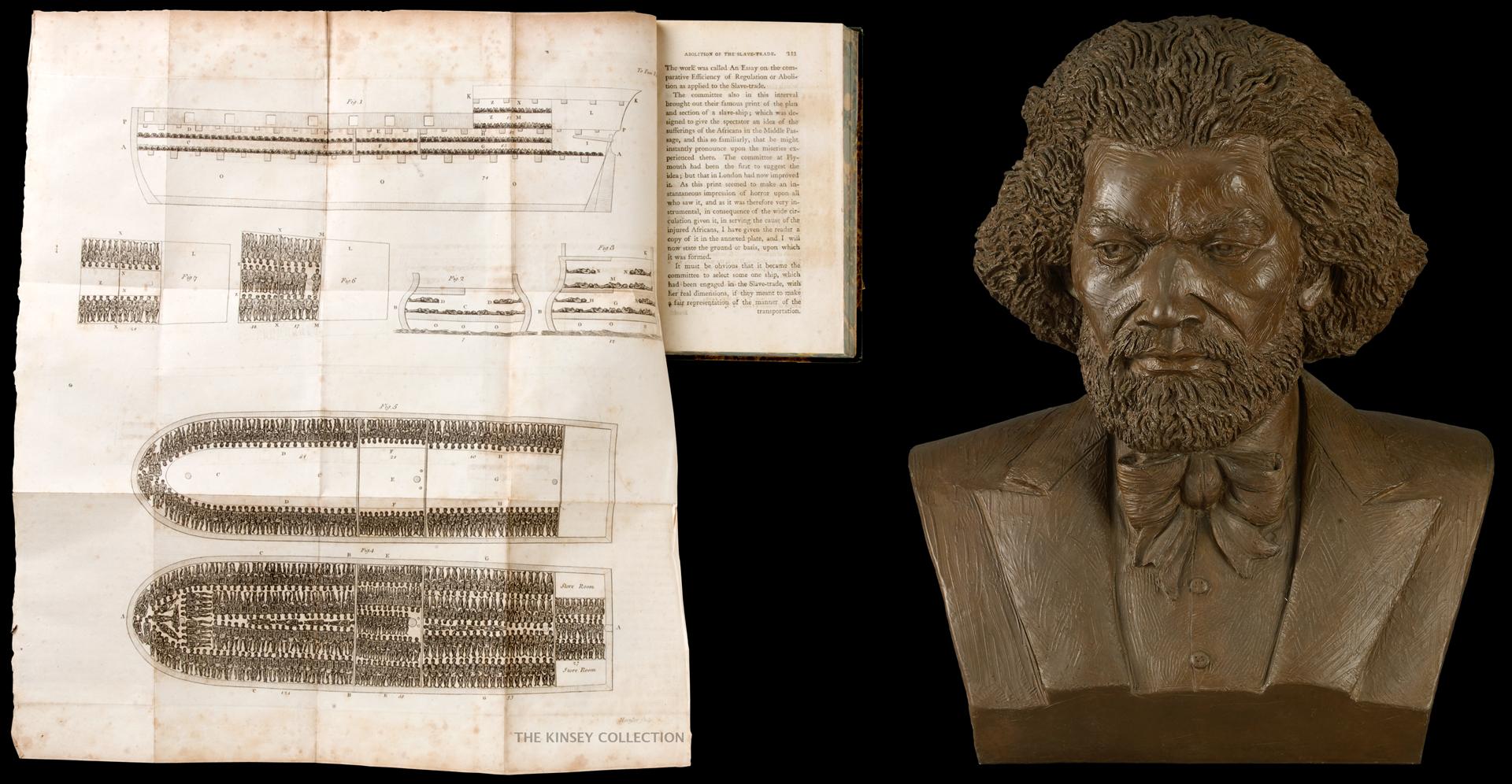

What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July: “Black citizenship is not valued at the same level as white citizenship is, and we absolutely know it,” says Bernard Kinsey.

The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament, by Thomas Clarkson, 1808, ‘Frederick Douglass,’ 2003, Tina Allen,

Reinvesting in the Black community is just one part of the path forward. Some of the work also requires acknowledging Black’s contributions to America and throughout the diaspora. And this is where the Kinsey Collection has had a tremendous impact.

“The myth of absence” permeates all aspects of American life, Kinsey notes. From corporations to the White House, there is a notion that Black people are invisible. The myth suggests that “Blacks are not a part of the dialogue, the picture, the narrative of this country.” The art and artifacts in the Kinsey Collection reveal the breadth and depth of the Black journey and offer insight and hope for overcoming America’s systemic racism.

“I love seeing Black Lives Matter because it shows we have agency,” Kinsey says. “Black citizenship is not valued at the same level as white citizenship is, and we absolutely know it.”

Many of the names of African American achievers have been lost or intentionally written out of history. The Kinseys have created a platform for unknown artists lost to whitewashed history, deliberately featuring those who have been erased and overlooked.

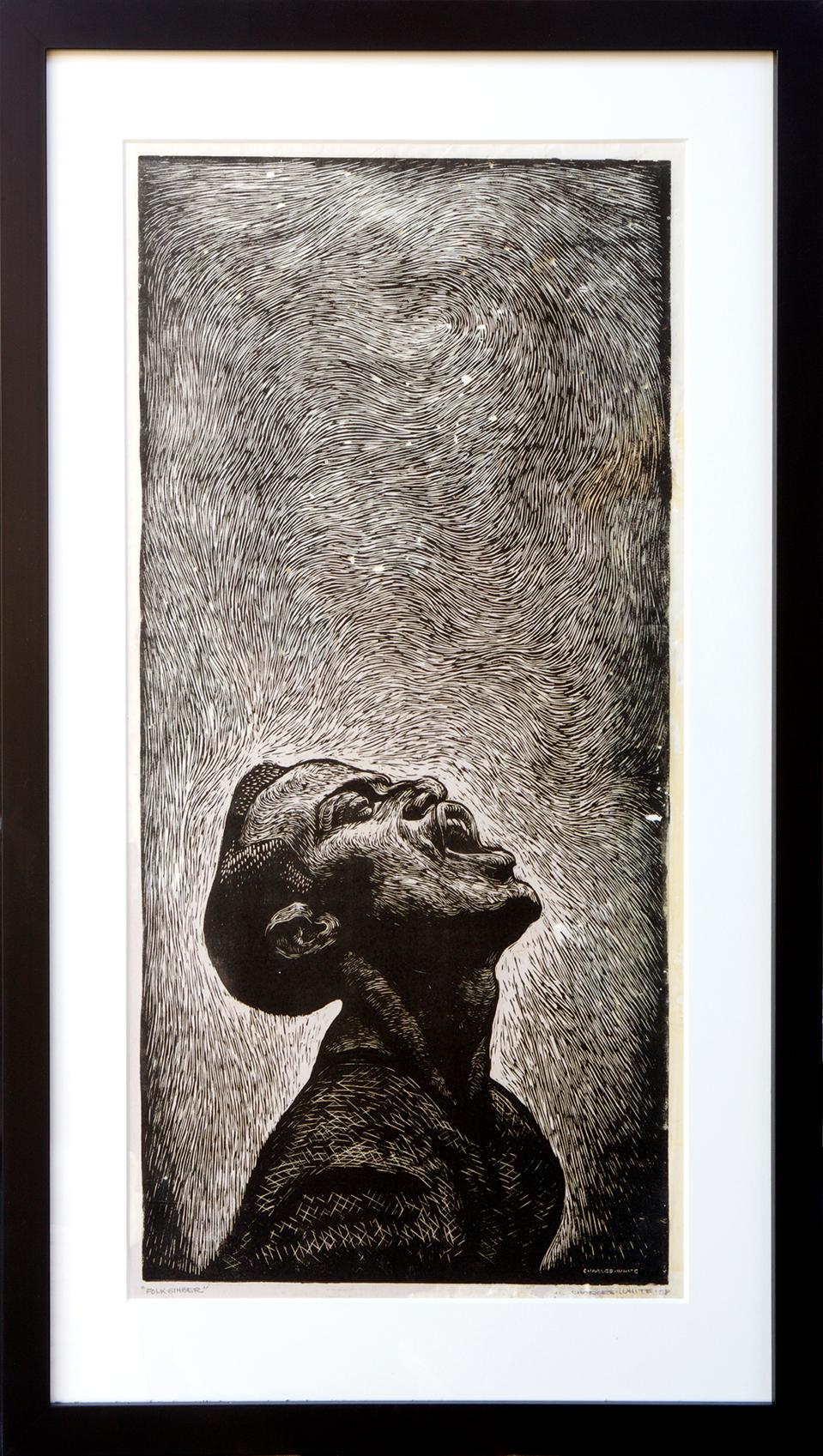

Say It Loud: “I love what I see,” Bernard Kinsey says, “because there are so many people involved in this struggle all over the world.”

‘Folk Singer,’ 1953, Charles White

“In his work, Bill Dallas is an activist of sorts,’ Shirley Kinsey says of the Black painter whose Blue Jazz is featured in the collection. “He’s been involved in a type of protest there because he feels he’s never been accepted as a good artist.”

While the fight for justice and equality has been ongoing, Kinsey says he’s never seen an awakening quite like this current movement. “I hope we’ll be able to get at [police reform] while we have this momentum because white America has a way of going back to sleep on this [race] question and the energy that’s being expended right now,” Kinsey says. “I love what I see because there are so many people involved in this struggle all over the world.”

As communities around the world awaken to the struggles that Black people face, Kinsey believes that part of how America heals is through art and reclaiming the narrative that positions Black people as less than.

“There was a time that as a Black teen I started getting close to certain pitfalls and traps,” Khalil Kinsey, who now manages and curates the collection, says of his parents’ mission to educate him on Black history. “But these foundational elements always kept me from making certain decisions.”

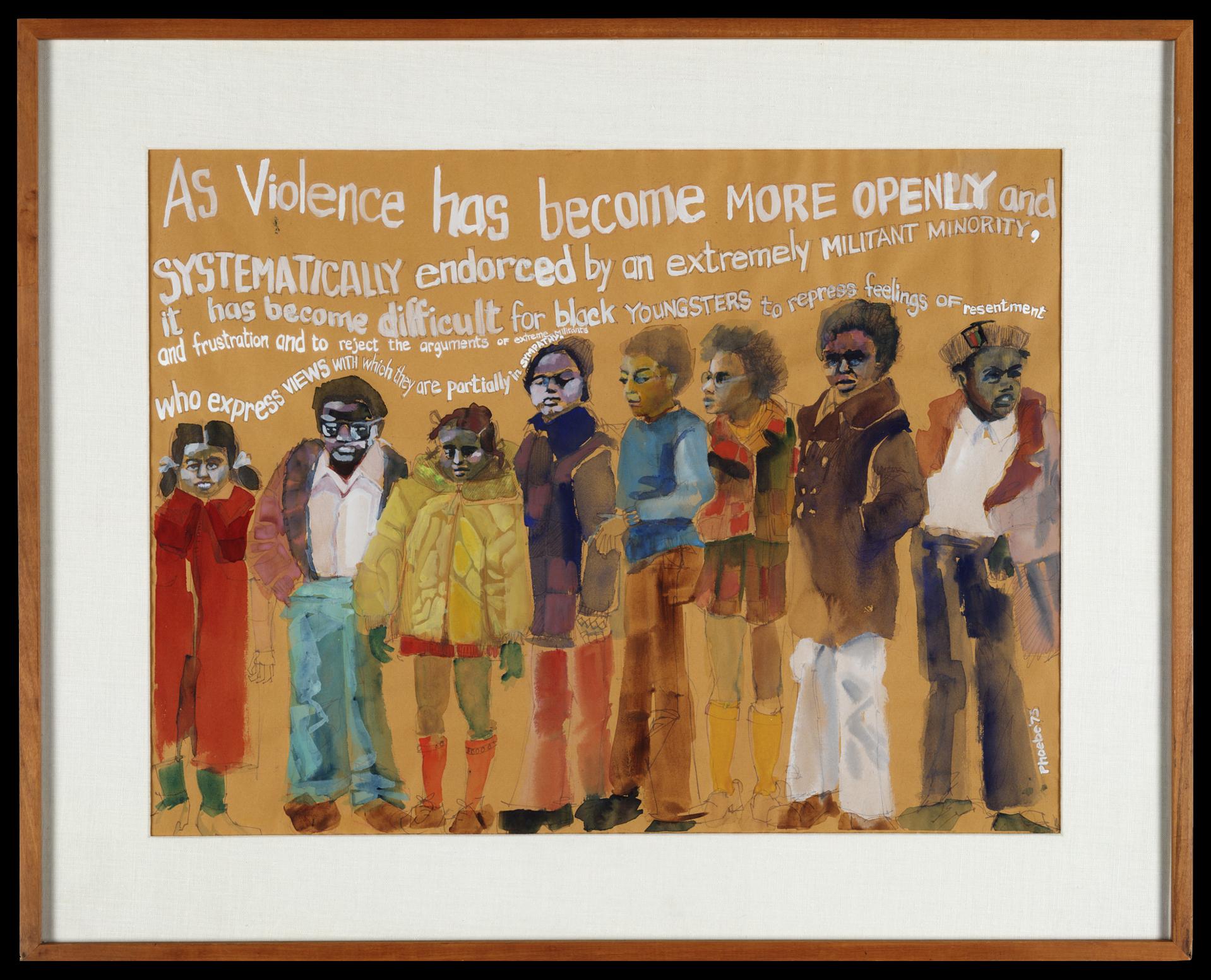

Painted Word: Phoebe Beasley’s work “conveys frustration without an outlet, and the influence of American violence,” says Kahlil Kinsey.

‘As Violence,’ 1973, Phoebe Beasley, American

He says many of his Black friends weren’t as lucky to have this positive influence and often didn’t have an outlet for their feelings about injustice and experiences of racism. Years before the killing of George Floyd, it was Phoebe Beasley’s 1973 painting As Violence that embodied the rage and despair many young Black Americans experience.

“It conveys frustration without an outlet, and the influence of American violence,” Khalil Kinsey continues. “It’s the reflection of young people who understand that they’re under siege but don’t know how to articulate it in other ways.”

Through his life’s work and his collection, Bernard Kinsey hopes that Black people will continue to exercise agency and become the authors of their own stories. Above all, he longs for fiscal policies that demonstrate Black lives, in fact, matter.

“It’s amazing to me still, two young kids from Florida, who came to California to do what we’re doing. I don’t take it for granted, and we have to share it,” Shirley Kinsey said. “When we’re gone this will carry on.”

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel